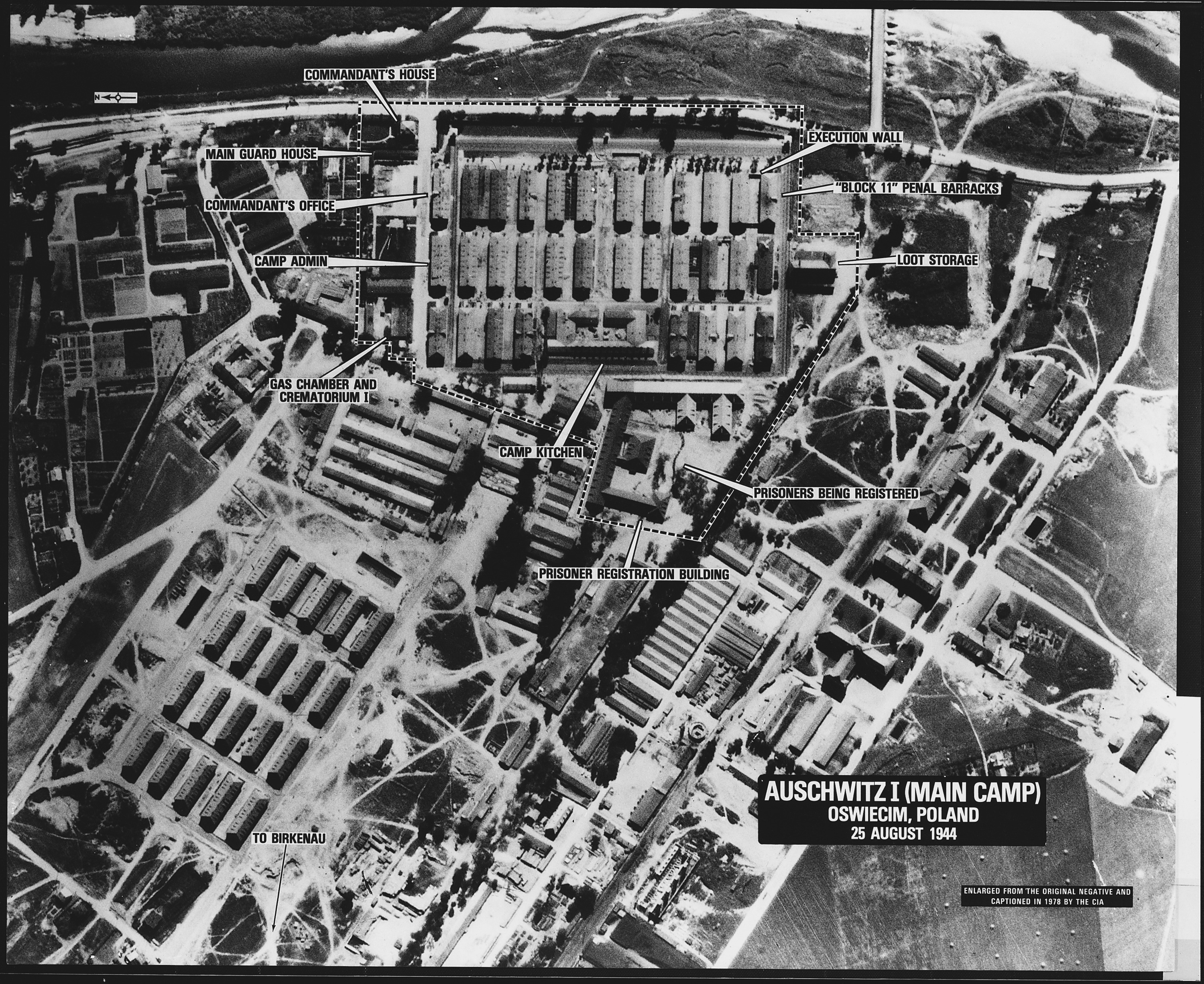

Auschwitz escape 1944 — the case of Jerzy Bielecki and Cyla Cybulska — is one of the best documented prisoner escapes from the camp. With help from fellow inmates, Bielecki obtained parts of an SS uniform and a forged pass; posing as a guard, he escorted Cybulska out in daylight. This article explains who they were, how the plan worked, and what happened afterwards. For broader background see the USHMM overview Auschwitz and our guides: Origins of Auschwitz, the Auschwitz map and structure, Auschwitz Birkenau, Auschwitz resistance and Victims and Survivors.

Who were Jerzy Bielecki and Cyla Cybulska?

Jerzy Bielecki was a Polish political prisoner deported with the first transport of Poles in June 1940. Cyla (Tzila) Cybulska, a Jewish prisoner transferred to Birkenau in 1943, worked near the camp’s grain warehouse. Despite strict segregation and prohibitions on contact, they met while working in adjacent areas. Over months they developed a clandestine relationship and started to plan an exit that could pass as a legitimate transfer under SS authority — the only kind of movement that routinely crossed checkpoints in daylight.

Planning the Auschwitz escape 1944

The plan relied on three elements: appearance (uniform), paperwork (pass), and behaviour (confident timing through gates). Fellow prisoner Tadeusz Srogi helped assemble parts of an SS uniform and obtain a pass template; inmates in the camp printing office could reproduce the look of current paperwork. Bielecki observed traffic patterns at gates and identified a route via the Raisko area, where work detachments and vehicles often moved between zones. Contemporary accounts gathered by the museum’s researchers confirm the importance of documentation and cover stories in successful escapes; see the Auschwitz Museum page on escapes from the camp (PL).

Crucially, the forgery matched the week’s routine: guards were issuing green passes. From a hide above the grain warehouse Bielecki retrieved a green blank, then completed it with a copying pencil — route, purpose, number of escorts, name of the SS controller, time and date. He signed the identity “Helmuth Steiner, SS-Rottenführer” and set the date to 21 July 1944. The script they rehearsed kept the initiative: the pass would be shown only if requested; tone and pace had to mirror an authorised transfer.

The day itself: 21 July 1944

On the afternoon of 21 July 1944 Bielecki slipped away from his work detail, changed into the SS uniform and went to Cyla’s workplace. Introducing himself as an officer on duty, he called her out for “interrogation”. Walking side by side, they headed towards Raisko. At the checkpoint, the forged pass — prepared in advance — raised no suspicion, and they crossed beyond the outer guard chain. From there they moved on foot, mostly at night, avoiding roads and patrols while seeking help from trusted contacts.

Before changing, Bielecki gave Cyla a pre-arranged hand signal from the balcony; he also secured a short, plausible errand in the vicinity of the warehouse to fit into the day’s routine. At the Kontrollstelle the NCO glanced at the paper and waved them through — the kind of brisk “carry on” that followed when everything looked routine. Confidence and economy of movement did the rest.

Aftermath: hiding, separation and survival

Once outside, the dangers changed but did not vanish. After dark they nearly strayed into a barrage-balloon unit near the Buna-Werke construction zone, and later came under fire near Zator from a night watch. Help followed: in Bachowice they found shelter and a guide across the “green border” around Brzeźnica; they crossed the Vistula by ferry near Czernichów and eventually reached Bielecki’s family contacts in Muniakowice. From there the pair separated for safety — Cyla hid with a Polish family until the end of the war; Bielecki joined a Home Army partisan unit.

Wartime chaos and broken lines of communication led each to believe the other had died. Only in 1983 did they meet again at Kraków airport — Bielecki greeted Cyla with 39 red roses, one for each year apart. In 1985 he was recognised by Yad Vashem as one of the Righteous Among the Nations.

Why this Auschwitz escape matters

The Bielecki–Cybulska case shows how observation, forged documents and credible performance could temporarily overcome the camp’s control system — when coordinated across different work details and supported by fellow prisoners. It is one of several documented escapes that both carried information outside and sustained hope inside. For wider patterns of escapes and reprisals, see the Auschwitz Museum’s overview of escapes (PL) and the USHMM entry on Auschwitz.

Sources and further reading

Institutional overviews and reference material include: the USHMM encyclopedia article on Auschwitz, the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum page on escapes (PL), Yad Vashem’s portal on the Righteous Among the Nations, and the official website dedicated to Jerzy Bielecki (jerzybielecki.com).

Read next

Auschwitz resistance · Auschwitz escape — 20 June 1942 · Auschwitz Birkenau · Victims and Survivors